Case

Richard is 75 years old with bilateral knee arthritis and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). For his GERD, 12 years ago he was started on pantoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), but his last family doctor retired so he was never reassessed. He remembers having quite a bit of heartburn and the pantoprazole resolved his symptoms. He was mildly obese for much of his adult life, but since retiring 10 years ago, he has worked to eat healthier, with good results, having lost about 15 pounds and being able to keep it off. He continues to be fairly active and maintains a balanced Mediterranean diet.

Issue

Richard has been on a PPI for 12 years and his symptoms have not been an issue. He has made lifestyle changes in the last 10 years. When should his PPIs be reviewed?

Background

PPIs are the fifth most common prescription in Canada.1 However, PPIs are not benign and can have a number of side effects and long term risks. These risks, although fairly low, can include clostridium difficile infection, pneumonia, chronic kidney disease and vitamin and mineral deficiencies (hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesemia, vitamin B12 deficiency).2 In addition, there is a possible increased risk of gastric cancers (especially in the case of helicobacter pylori infections).3

The risk of fracture is also commonly cited for use of PPIs. In 2010, the US FDA required labelling of PPIs to include a warning of possible increased risk of bone fracture, though there is not enough evidence to distinguish if the negative effects on bone health from PPIs are more related to nutritional deficiencies, such as impaired calcium absorption due to increased gastric pH.2 The US FDA later retracted the warning about fractures for over-the-counter PPIs, as there was insufficient evidence for bone mineral density changes due to low dose, short-term usage of PPIs.2 Regardless of the side effects of PPI use, an ongoing challenge is that PPIs are often used inappropriately and longer than indicated in many patients.4

Indications for PPI

There are multiple indications for PPIs including:

- healing of peptic ulcers

- management of peptic ulcer related gastrointestinal bleeding

- treatment of helicobacter pylori

- prevention of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcers

- management of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

- erosive esophagitis

- non-erosive reflux disease

- functional dyspepsia.5

In many instances, a short course of PPIs followed by reassessment (and either decreased dosage or stoppage of use) is recommended.1 Indications for long-term use of PPIs are for when a compelling reason exists. These include:

- refractory GERD

- Barett’s esophagus

- erosive esophagitis

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

- idiopathic chronic ulcer

- gastroprotection with daily NSAID use, if at moderate or high risk for ulcer.1

Risk factors for ulcers in the context of NSAID use include:

- age >/= 65 years old

- high dose NSAIDs use

- history of uncomplicated ulcer

- concurrent aspirin use (including low dose aspirin)

- corticosteroid use

- anticoagulant use.

Three or more of these risk factors indicates that the risk of ulceration is high, and one to two of these risk factors indicates a moderate risk of ulceration.1 A history of a previous complicated ulcer is also considered high risk.1 Unfortunately, PPIs are often used longer than indicated or recommended,4 so an approach to deprescribing would be helpful in eliminating unnecessary usage.

Management

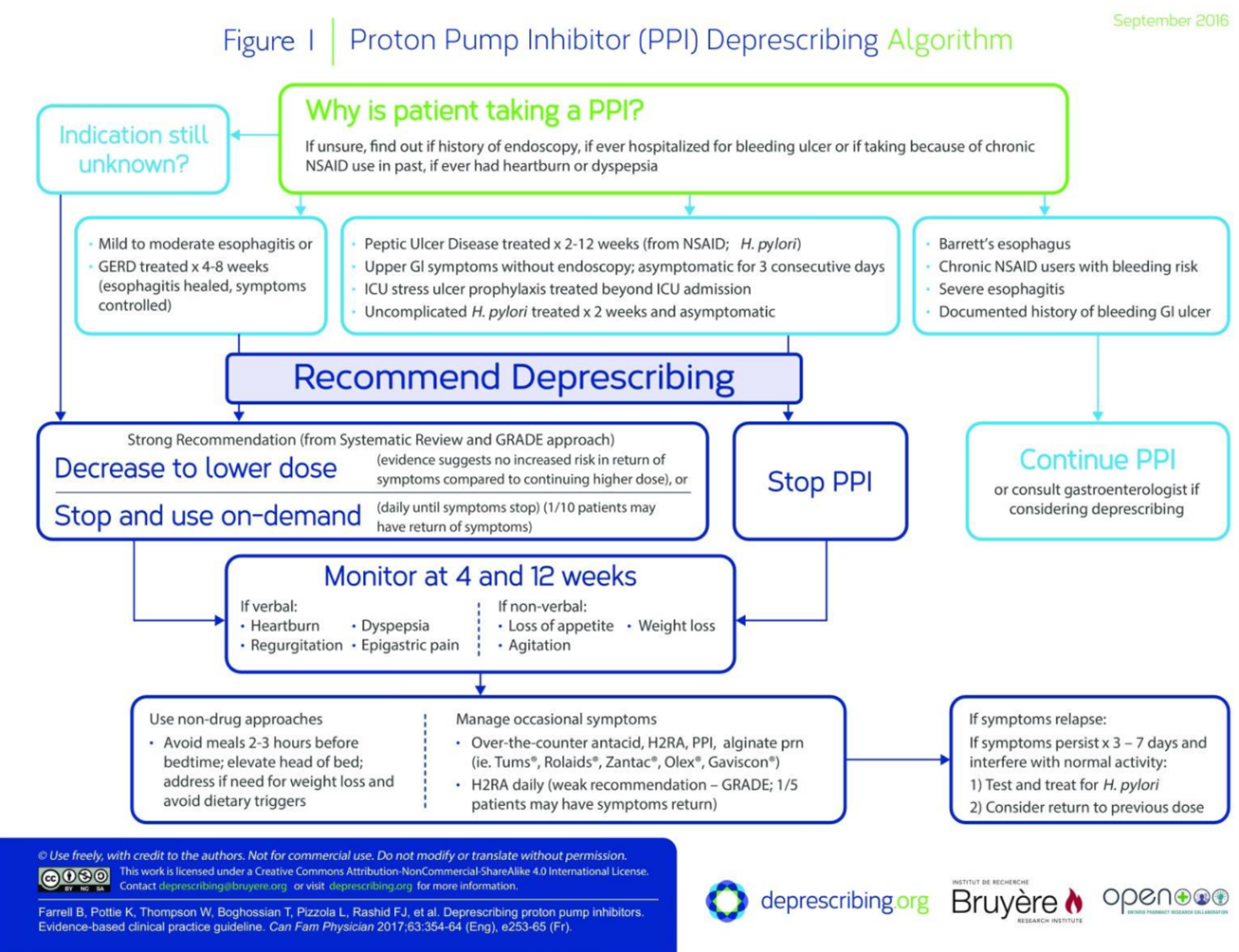

Although at this time, there does not appear to be conclusive evidence on the best approaches in deprescribing in the elderly, studies showing more efficacy do tend to favour having a component of medication review.6 This may be a tool that can be done at regular intervals, given the recommendation by Choosing Wisely Canada to review PPI prescriptions with patients on a yearly basis.7 Although not specific to the elderly population, an evidenced-based clinical practice guideline for deprescribing has been published in the Canadian Family Physician journal.1 In this guideline’s approach, the initial step is to first assess why a patient is taking a PPI, and if the indication is unknown, then to decrease the dose or stop and use on-demand PPIs.1 If there was initially an indication (such as helicobacter pylori, peptic ulcer disease or other) which has been adequately treated, stopping PPIs followed by symptom monitoring at four and 13 weeks is recommended.1 Non-pharmacologic approaches such as avoiding meals two to three hours before bed, elevating the head of the bed, managing dietary triggers and addressing weight loss, if indicated, should also be part of the management plan.1 Occasional symptoms can be managed using as-needed medications, and there can be consideration for return to PPI use on reassessment if there is symptom relapse.1 Should there be a compelling indication for long-term use of PPIs such as Barrett’s esophagus or severe esophagitis, then continued PPI use is indicated, with consultation to gastroenterology if deprescribing is considered.1 A diagram outlining the Canadian Family Physician 2017 deprescribing guideline is referenced below.1

Recommendations

Richard has been taking PPIs for 12 years for his GERD without reassessment, and he has had a significant change in lifestyle. Ideally, he would have been reassessed for symptoms after four to eight weeks of his initial treatment,1 with his dose either stopped or decreased to the lowest effective dose where possible. Additionally, should he have needed ongoing PPIs, an annual review of his PPIs would have been helpful for earlier deprescribing, especially after he had a significant lifestyle change. One possible way that may have allowed for an earlier medication review for Richard is to use an automated reminder using a clinic’s electronic medical record (EMR) to review PPIs at the appropriate intervals in order to help with minimizing polypharmacy.7 In Richard’s case, he found a new family physician after his last one retired and had a medication review with the clinic’s pharmacist. His PPI use was flagged and then deprescribed. On reassessment at four and 12 weeks, he had no recurrence of symptoms.

PPI Deprescribing Algorithm1

References

- Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, Boghossian T, Pizzola L, Joy Rashid F, et al. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors. 2017

- Jaynes M, Kumar AB. The risks of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: a critical review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018 Nov 19;10:2042098618809927.

- Cheung KS, Leung WK. Long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: a review of the current evidence. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2019 Mar 11;12:1756284819834511.

- Walsh K, Kwan D, Marr P, Papoushek C, Lyon WK. Deprescribing in a family health team: a study of chronic proton pump inhibitor use. J Prim Health Care. 2016 Jun;8(2):164–71.

- Strand DS, Kim D, Peura DA. 25 Years of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Review. Gut Liver. 2017 Jan;11(1):27–37.

- Wilsdon TD, Hendrix I, Thynne TRJ, Mangoni AA. Effectiveness of Interventions to Deprescribe Inappropriate Proton Pump Inhibitors in Older Adults. Drugs Aging. 2017 Apr 1;34(4):265–87.

- Bye-Bye, PPI. Choosing Wisely Canada; 2019.