Contributed by:

Dr. Vivian Ewa, MBBS, CCFP (CoE), PG DipMedEd, FCFP, FRCP Edin Section Chief- Seniors Care and Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Calgary. - View bio

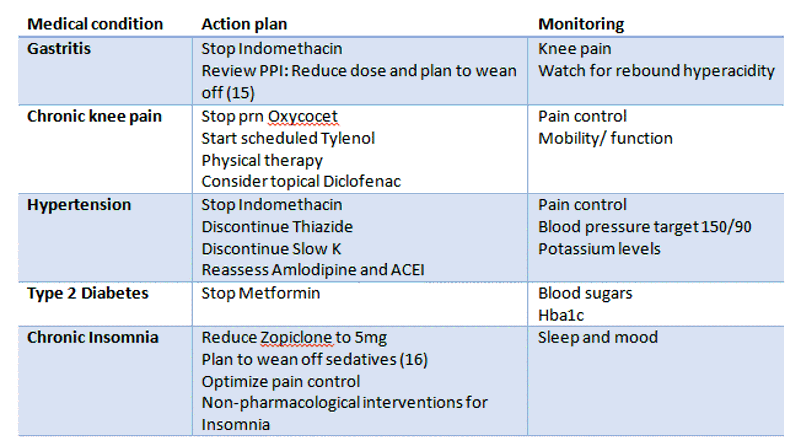

Mrs. Poly is a 78-year-old woman who resides in a seniors' retirement home. Her past medical history is significant for hypertension; type 2 diabetes; dyslipidemia; coronary artery disease with previous NSTEMI; gastritis; hypothyroidism; chronic knee pain and insomnia. Her medications are listed in figure 1, below.

Figure 1

Background

About one-in-four seniors in Canada have three-or-more chronic medical conditions. Seniors with one-to-two medical conditions take three-to-four medications, while seniors with three-or-more conditions take six-or-more medications.(1) The single most important predictor of harm in a patient is the number of drugs they take.(2)

Physiological changes associated with aging, frailty and increased use of drugs contributes to the increased risk of adverse drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in the elderly, which increases the risk of harm and even death.(3) The application of clinical practice guidelines increases the risk of multiple drug use in the elderly and may not always be appropriate given the low representation of the elderly in clinical drug trials.(4, 5) Physicians may be reluctant to stop medications especially if not prescribed by themselves and where there are multiple prescribers.(6) A systematic approach to medication review within a comprehensive geriatric assessment and incorporating the patient’s wishes can lead to successful deprescribing in the elderly population.(7)

This article provides a basic framework to tackle therapeutic competition in the elderly. The first section discusses the comprehensive geriatric assessment including a comprehensive medication review that informs clinical decision making on deprescribing. The second section discusses implementation of changes and strategies for successful outcomes.

Clinical decision-making phase

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)

CGA is a multicomponent assessment that involves creating a plan for treatment then follow up in the older adult.(8) Usually done in a multidisciplinary setting, components of the CGA may still be done in an office setting in collaboration with a trained interprofesional team. The CGA involves review of chronic medical conditions, assessment of mood, functional status, mobility, cognitive function, nutritional status, medications and social supports. The clinical frailty scale(9) or the Edmonton frailty scale(10) are tools that can use information generated in the CGA to determine frailty status.

Comprehensive medication review

A comprehensive medication review involves obtaining the list of all medications being used by the patient including eyedrops, topicals and over the counter medications. This review contains indications for use, dosage, date of last dose taken and any side effects. Medication reconciliation (med rec) has been shown to reduce adverse outcomes.(11) Once med rec has been completed, the next step is to identify any prescription cascades.

Identifying prescription cascades

A prescription cascade occurs when an adverse drug reaction is misinterpreted as a new medical condition resulting in a new prescription.(12) See Figure 2 below for an example of a prescription cascade in Mrs. Poly’s case.

Figure 2

Medication appropriateness

The next step in the decision-making stage is looking at medications for appropriateness. The medication appropriateness index is a helpful tool that allows you to identify inappropriate medications by asking 10 questions.(13) Key questions explore the indication, recognized effectiveness, current dosage and duration, duplication, cost and significant adverse effects. Med rec helps in answering some of these questions.

In some cases, medications may be appropriate but may still be discontinued when consideration is given to life expectancy, goals of care and potential benefits of medications in late life.(4) This strategy incorporates time until benefit, treatment target and goals of care to inform the decision to move towards a palliative versus curative approach.(4)

Deprescribing phase

Action plan

Having an action plan for what medications will be changed or discontinued increases the likelihood of success. In our example of Mrs Poly we would be managing her chronic knee pain, which is likely due to osteoarthritis. The action plan would be stop the prn Oxycocet and start regular scheduled Tylenol and consider topical diclofenac to optimize pain control. Mrs. Poly may also benefit from non-pharmacological interventions such as physical therapy, e.g., quadricep strengthening exercises.

Monitoring

In addition to an action plan, parameters to be monitored should be clearly identified and discussed with the patient and/or caregivers. Monitoring should cover withdrawal symptoms and adverse outcomes in addition to benefits. This increases the chances that recommendations will be followed. It is also important to agree on treatment targets and overall goals with the patient and/or caregivers. Regarding our example of Mrs. Poly, pain will be monitored with the goal to optimize pain control and function.

Where multiple prescribers are involved, this practical approach to stopping medications, i.e., deprescribing, can be done safely with successful outcomes.(14)

Back to the case

Following a CGA, we find that Mrs. Poly has mild cognitive impairment; she is independent with all IADLs and most ADLs, but needs assistance with bathing, housekeeping and meal preparation due to chronic knee pain, which limits her mobility. She has been hospitalized twice in the past year for falls and has adequate social supports. She was started on indomethacin for possible Calcium Pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition (CPPD) 20 years ago, and shortly after this she developed hypertension and was started on amlodipine. She was started on hydrochlorothiazide for ankle swelling about eight years ago and Lasix was added two years ago to help manage leg swelling. She had a myocardial infarction 10 years ago and was started on Clopidogrel as she was intolerant of aspirin. She does not have history of heart failure. On clinical assessment her blood pressure was 100/ 60 with a heart rate of 60 beats per minute. There is evidence of bilateral knee osteoarthritis. She is mildly frail on both the Clinical frailty scale(9) and Edmonton frail scale(10). Her recent Hba1c is 7% and she has normal electrolytes with mild renal impairment. Her complete blood count shows a hemoglobin of 100g/dl with normal iron indices.

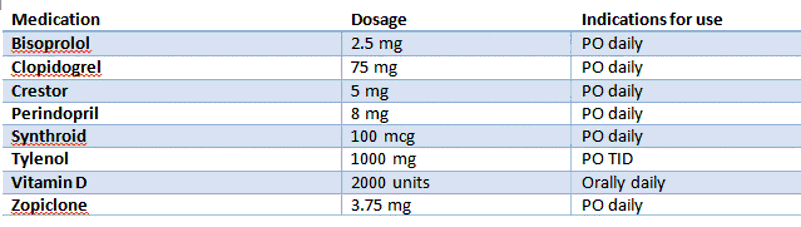

Figure 3 below describes the deprescribing plan used for Mrs Poly.

Figure 3

Changes were done over several months. See Figure 4 for Mrs. Poly’s updated medication list at six months.

Figure 4

Bottom line

Medications can be safely stopped in the older adult patient. A comprehensive geriatric assessment which incorporates the clinical assessment with review of medication, functional status and cognition, while incorporating patient’s goals of care and prognosis of complex multimorbidity can inform appropriate prescribing in older adults. Tools such as the medication appropriateness index and deprescribing.org (17) can help in deprescribing. A practical approach that includes an action plan and monitoring ensures that this is done safely.

References

- Canadian Institute for Health Informaiton. Seniors and the Helath Care System: What is the Impact of Multiple Chronic Conditions? Ottawa; 2011.

- Steinman MA, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Komaiko KD, Schwartz JB. Prescribing quality in older veterans: a multifocal approach. Journal of general internal medicine. 2014;29(10):1379-86.

- Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175(5):827-34.

- Holmes HM, Hayley DC, Alexander GC, Sachs GA. Reconsidering medication appropriateness for patients late in life. Archives of internal medicine. 2006;166(6):605-9.

- Mutasingwa DR, Ge H, Upshur RE. How applicable are clinical practice guidelines to elderly patients with comorbidities? Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(7):e253-e62.

- Anthierens S, Tansens A, Petrovic M, Christiaens T. Qualitative insights into general practitioners views on polypharmacy. BMC family practice. 2010;11(1):65.

- Sergi G, De Rui M, Sarti S, Manzato E. Polypharmacy in the elderly. Drugs & aging. 2011;28(7):509-18.

- Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Rubenstein L, Adams J. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. The Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1032-6.

- Rockwood K, Xiaowei S, Chris M, Howard B, David BH, Ian M, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. 2005.

- Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age and ageing. 2006;35(5):526-9.

- Medication Reconciliation (MedRec) - Topics | CPSI. 2017.

- Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Optimising drug treatment for elderly people: the prescribing cascade. Bmj. 1997;315(7115):1096-9.

- Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, Weinberger M, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1992;45(10):1045-51.

- Farrell B, Merkley VF, Thompson W. Managing polypharmacy in a 77-year-old woman with multiple prescribers. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2013;185(14):1240-5.

- Evidence-based deprescribing algorithm for proton pump inhibitors OPEN: the Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network 2017 [Available from: www.open-pharmacy-research.ca/evidence-based-ppi-deprescribing-algorithm/.

- Evidence-based deprescribing algorithm for benzodiazepine receptor agonists OPEN: the Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network 2017 [Available from: www.open-pharmacy-research.ca/evidence-based-deprescribing-algorithm-for-benzodiazepines/.

- Deprescribing. Deprescribing.org - Optimizing Medication Use: @Deprescribing; 2017 [Available from: deprescribing.org/.