Contributed by: Jasneet Parmar, MBBS, Dip.COE (Jasneet

Cynthia, who is 80-years-old, visits you, her family physician for follow-up after discharge from hospital. She is accompanied by her daughter. Cynthia was recently discharged after a four-week stay in hospital for complications from coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure. She also suffers from diabetes, hypertension and osteoporosis. Her discharge diagnosis includes mild cognitive impairment. Towards the end of her 15-minute visit with you, you reviewed her medications and counted 12 of them!

Issue

In the context of the physician’s clinic, what is the best strategy for medications management amongst seniors at transitions of care?

There are many issues to consider with medications management in seniors.

- The family physician has limited time to address all of the patient’s concerns, including optimizing medications.

- The older adult with multiple comorbidities will typically have a long list of medications. Seniors with three or more chronic conditions are taking an average of six prescription medications (CIHI, 2011). Polypharmacy, (specially, more than five medications used concurrently), is associated with increased incidence of drug-related adverse events. In 2010-2011, one in 200 Canadian seniors (more than 27,000 seniors) had hospitalizations related to adverse drug reactions (CIHI, 2013).

- Adverse events including medication errors are common in the post-discharge period. The health system currently has significant deficiencies in safety at discharge (Snow, 2009). Medication errors tend to occur in transitions of care (Desai, 2013).

Medication management in the family physician’s office is being done through a variety of interventions (Kucukarslan, 2011) that may include:

- Collaboration among health care providers – physicians or prescribers, nurses or care coordinators, pharmacists and case workers.

- Telephone or face-to-face follow-ups.

- Creation of algorithms and treatment plans.

What is Medication Reconciliation (MedRec)?

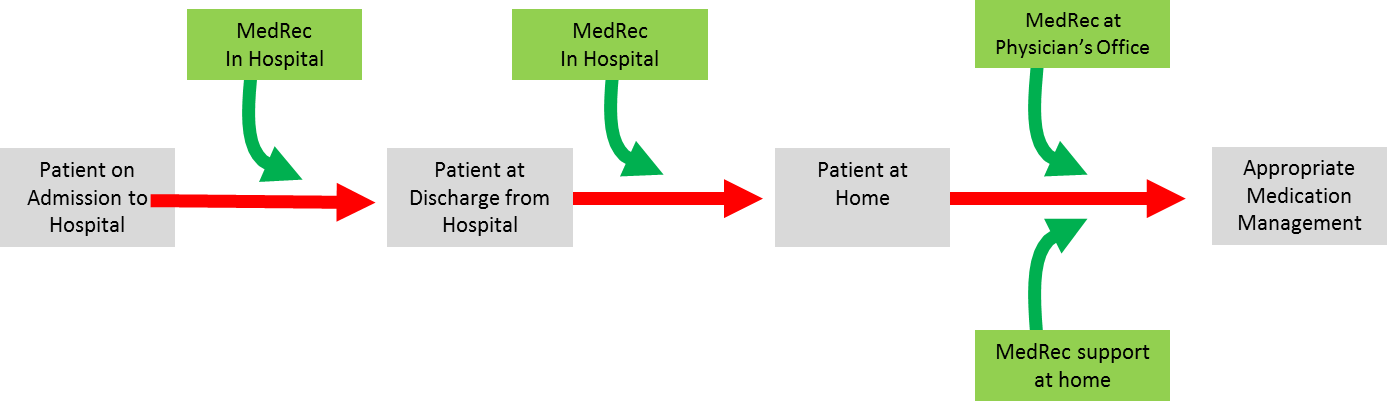

MedRec has been identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as part of their High 5s project, highlighting the top five safety priorities internationally. It is “a formal process (by) which health care providers work together with patients, families and care providers to ensure that accurate and comprehensive medication information is communicated consistently across transitions of care.” (Institute of Safe Medication Practices in Canada: ISMP) MedRec is fundamental to medication management and builds on the medication history- taking physicians have been using for years. It is a major safety initiative to improve communication about medications as patients transition through health care settings, and it helps physicians make the appropriate (de)prescribing decisions for their patients. MedRec is an opportunity to encourage patients to be involved in medication safety (Frank, 2014). MedRec requires: (See Figure 1)

- Best Possible Medication History (BPMH): Generation of a complete and up to date medication list including drug name, dosage, route and frequency.

- Reconciliation of the medication list and identification of discrepancies.

- Documentation and communication.

Figure 1. Process of Medication Reconciliation.

Where is MedRec being used?

Alberta Health Services and Covenant Health are using MedRec during hospital admission and discharge, as patients transition between care settings (see Figure 2). Case managers are responsible for MedRec at admission for clients on homecare in the community. They are expected to provide the same when their clients are being discharged home from hospital. Also, a number of Primary Care Networks (PCNs) in Alberta have started to use the materials offered though the online portal for resources and tools.

Figure 2. MedRec at the Transitions of Care.

MedRec is an Accreditation Canada Required Organizational Practice (Accreditation Canada, 2012)

More about MedRec

Learn more about MedRec by clicking through the tools and resources provided below.

- Institute of Safe Medication Practices in Canada (ISMP) (http://www.ismp-canada.org/medrec/)

- World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Patient Safety in support http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/solutions/high5s/h5s-fact-sheet.pdf

- Alberta Health Services – Medication List Campaign (http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/info/page12614.aspx)

- Alberta Health Services – Medication Reconciliation eLearning Module (http://www4.albertahealthservices.ca/elearning/wbt/MedRec/index.html)

- Alberta.ca – Medication Lists and Tools (https://myhealth.alberta.ca/alberta/Pages/medicine-tracking-tools.aspx )

- Alberta Health – Pharmacy Services and Prescription Drugs (http://www.health.alberta.ca/services/pharmacy-services.html)

References

- Accreditation Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information, the Canadian Patient Safety Institute, and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada. (2012). Medication Reconciliation in Canada: Raising The Bar – Progress to date and the course ahead. Ottawa, ON: Accreditation Canada.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Adverse Drug Reaction-Related Hospitalizations Among seniors, 2006 to 2011. Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2013 Mar. Available from https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/Hospitalizations%20for%20ADR-ENweb.pdf

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Seniors and the health care system: What is the impact of multiple chronic conditions? Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2011 Jan. Available from https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/air-chronic_disease_aib_en.pdf

- Desai R, Williams CE, Greene SB, Pierson S, Hansen RA. Medication errors during patient transitions into nursing homes: characteristics and association with patient harm. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011 Dec;9(6):413-22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.10.005. Epub 2011 Nov 13.

- Farrell B, Shamji S, Monahan A, Merkley VF. Clinical vignettes to help you deprescribe medications in elderly patients: Introduction to the polypharmacy case series. Can Fam Physician. 2013 Dec; 59(12):1257-8, 1263-4. PubMed PMID:24336529; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3860913. Available from: http://www.cfp.ca/content/59/12/1257.long

- Frank C, Weir E. Deprescribing for older patients. CMAJ. 2014 Dec 9;186(18):1369-76. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131873. Epub 2014 Sep 2. Review. PubMed PMID: 25183716; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4259770. Available from: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/186/18/1369.long\

- Kucukarslan SN, Hagan AM, Shimp LA, Gaither CA, Lewis NJ. Integrating medication therapy management in the primary care medical home: A review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011 Feb 15;68(4):335-45. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100405. Review. PubMed PMID: 21289329.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, Miller DC, Potter J, Wears RL, Weiss KB, Williams MV; American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians-Society of General Internal Medicine- Society of Hospital Medicine-American Geriatrics Society-American College of Emergency Physicians-Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Aug;24(8):971-6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0969-x. Epub 2009 Apr 3. PubMed PMID: 19343456; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2710485.

- Vira T, Colquhoun M, Etchells E. Reconcilable differences: correcting medication errors at hospital admission and discharge. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Apr;15(2):122-6. PubMed PMID: 16585113; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2464829.